Nick Cave has always been an enigma to me. Ever-present in my subconsciousness, yet never fully in focus. A living legend, a phenomenon I knew was around but one I never found access to in a meaningful way. And I also know there are many who would consider all of this some sort of blasphemy.

But how does one, in 2024, start to understand the vast wealth of a creative career that has lasted over half a decade by now? It seems like a futile exercise to recapitulate without doing the 67-year-old Australian gross injustice.

There are the broad, well-known, and certainly tragic stages: a long Heroine addiction, the loss of two of his children. But it feels voyeuristic and wrong to reduce an artist to only these moments.

Multi-Dimensional

There are other intrigues about Nick Cave worth exploring. His long-standing obsession with the Old and New Testament, his relationship with religion or God, or the fact that he has opened up his mind since 2018 in «The Red Hand Files», a blog/newsletter where Cave personally answers fan’s questions. Or as he describes it:

«The Red Hand Files has burst the boundaries of its original concept to become a strange exercise in communal vulnerability and transparency.»

These files are a treasure trove of insight into a contemplative and complex man: Cave describes himself as a minor-c conservative, voiced disdain for organised religion and atheism, radical bi-partisan politics and woke culture and supported the Masha Amini protests in Iran, as well as trans rights.

Now, I know, even simply listing these keywords defies the purpose, stripping away the thoughts and arguments that led to those convictions, and are therefore pretty useless. Empty shells, meaningless, ready to be attributed by our own biases definitions.

But it ultimately raises the question of whether «The Red Hand Files» may even be Cave’s boldest artistic work today. An antidote to simple answers in populistic times—in defiance of one-dimensionality.

Stubborn Complexity

However, all of this fades away into the background on October 22nd. On this particular evening, all attention flows towards the most recognised art of the multi-disciplinarian: music.

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds are inviting to a show at Zurich’s «Hallenstadion»—in their bags not only decades worth of material but also Wild God, the 18th (sic!) album released in August. Ten new songs—universally acclaimed. Andrew Trendell summarised for the «NME» that «once the godfather of goth, now a freewheelin' preacher of joy, Cave elevates above the grief on this colourful 18th album.»

I don’t dare to make a profound statement about the album—too unfamiliar am I with the heavy-bearing catalogue.

Yet, one notion I can’t shake, what I always stumbled upon, is a stubborn complexity. The compositions demand full commitment and attention, yet the signature is always clearly audible: from Where The Wild Roses Grow, the popular duet with Kylie Minogue, to Red Right Hand, becoming widely popular as the theme song to the series Peaky Blinders, and even the sinister, rambling epos that is The Mercy Seat.

For what it‘s worth, the decision is simple: Either you like the slight detachment of Cave‘s often more spoken than sung lyrics from the instruments… or you don‘t.

The Intimate Icon

Now I‘m sitting in Hallenstadion‘s sector G1, where the media has their spots, sitting left seen from the stage, with small tables to put down laptops, pens and paper. It‘s been years since I‘ve last sat here.

As I sip on my beer, glad I‘ll be (almost) comfortably seated for the following hours, I watch the stadium fill with people and a sliver of anticipation. But the gratitude wouldn’t last that long.

Into this still-settling scene drop The Murder Capital, a young post-punk band from Dublin, Ireland. Sometimes sad but often loud, raw, and angry, they fought an uphill battle against an ageing audience. Polite applause but few excited shouts.

At this point, you might be wondering: Where are the photos?

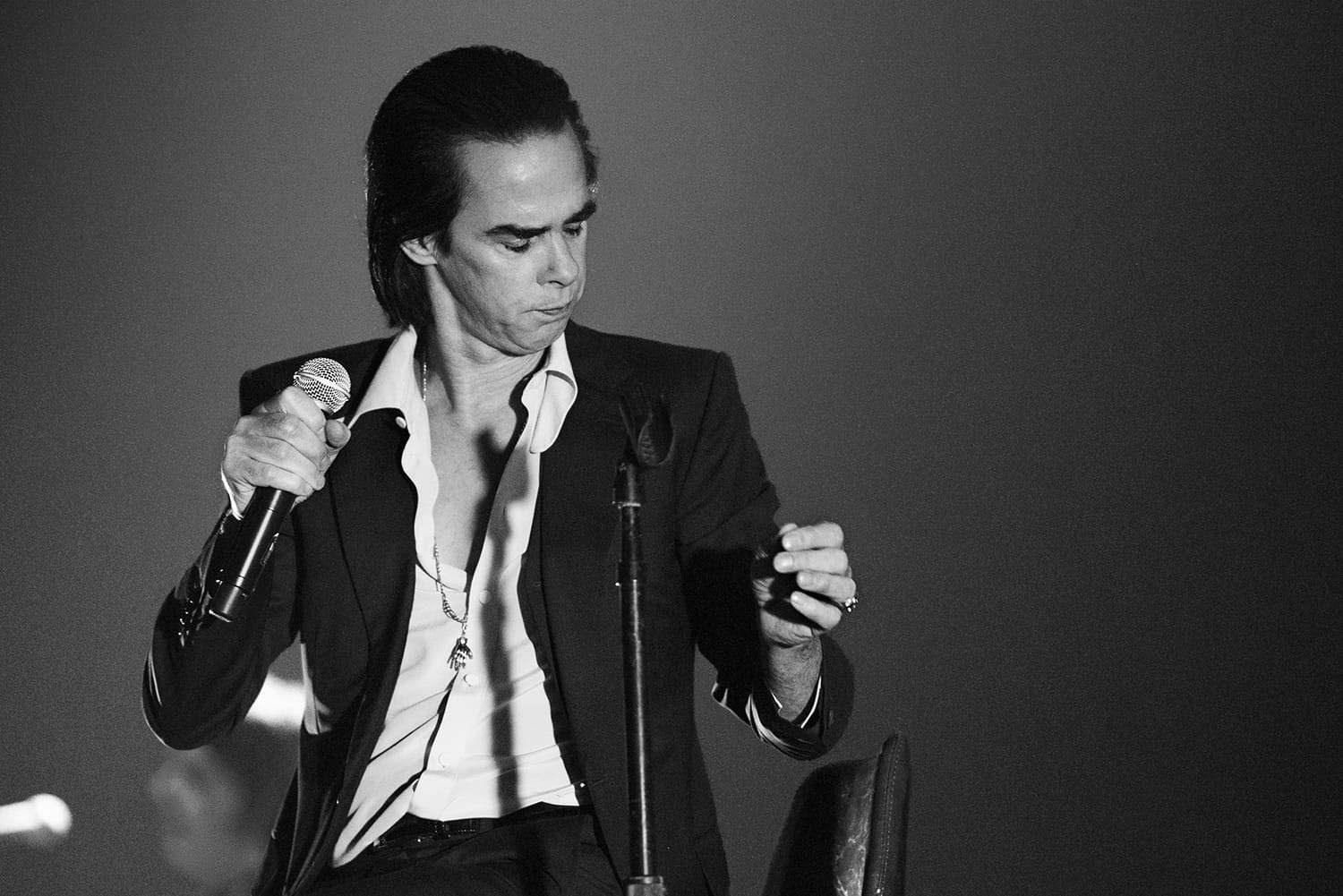

Unfortunately, our photographer, Evelyn Kutschera, came down with the flu, and we couldn‘t find a substitute on such short notice. But here‘s a visual break from the last concert in Zurich in 2017:

Coming back from grabbing another drink, my seat was taken by an elderly gentleman. We started talking, and he—like me—never had seen Nick Cave live before. He was convinced by a fan to come. We debated the downfall of journalism, especially in culture reporting, and about Thomas Wydler, the Swiss drummer of The Bad Seeds.

And then, for the next two and a half hours, I wished I didn‘t have a seat at all. I watched with envy down onto the crowd in front of the stage—closer to this explosion of energy and presence.

With nonchalance and verve, Cave moves up and down the stage, getting close to his fans while pleading and shouting and crying and screaming and singing. His music demands attention, undivided, and it gets it—one way or another. Throwing himself into some action poses for photos, Cave then said: «Now, put these fucking things away.»

The hall exploded with Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. They played through every phase of their oeuvre, from the archaic, brutal post-punk beginnings like 1984‘s From Her to Eternity or the hellish performance of Tupelo to the more experimental, genre-bending songs like Conversation, which morphs from brooding spoken-word to this almighty gospel.

And when Cave and his Bad Seeds got quiet, as in Bright Horses, the thousands of people became so silent one could hear a needle drop. Such deep was the emotion.

It‘s hard to do it all justice, and it‘s harder to make sense of it all. There is this rockstar somehow out of reach on that stage but at the same time as intimate and raw as a friend. A musical icon that isn‘t beyond us mere mortals but suffers and celebrates publicly.

Experiencing the absolute wildness of this show, I begin to understand people‘s fascination for Nick Cave. And that the «Red Hand Files» aren‘t some performative stunt but results from an inevitable need for connection. A need for authenticity, a desire to let things be complicated and hard and painful, and without an easy answer or cure.

But also a need to be seen, to be recognised as a human with all our difficulties and struggles. And a need for love. Nick Cave ended the concert alone at the piano, serenaded by the audience, with an Into My Arms.

But I believe in love

And I know that you do too

And I believe in some kind of path

That we can walk down, me and you